Exactly one hundred years ago, British diplomat Sir Mark Sykes and French diplomat François Georges-Picot, concluded the Sykes-Picot agreement, which divided the Middle East into two zones of influence with catastrophic consequences. This misguided attempt at political order is currently under serious challenge. Israel should be prepared to articulate its needs and concerns for when a new Sykes-Picot-style order is introduced.

One hundred years ago, two diplomats, one British and one French, concluded the Sykes-Picot agreement, which divided the Middle East into two zones of influence. The agreement became one of the cornerstones of the region, and gave the core area of the Middle East the shape it has assumed since the end of World War I. However, the political order founded a century ago by what were then British and French superpowers, including the regimes created and the borders delineated, is currently under serious challenge. The following article looks at the agreement through the lenses of the past and the present, and considers its prospects for surviving the political storms that currently engulf the region. It concludes with one recommendation: Israel should be prepared to articulate its ideas for a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. When a new “Sykes-Picot” order is created, it will almost certainly relate to that issue as well.

The Origins and Key Features of the Sykes-Picot Order (Itamar Rabinovich)

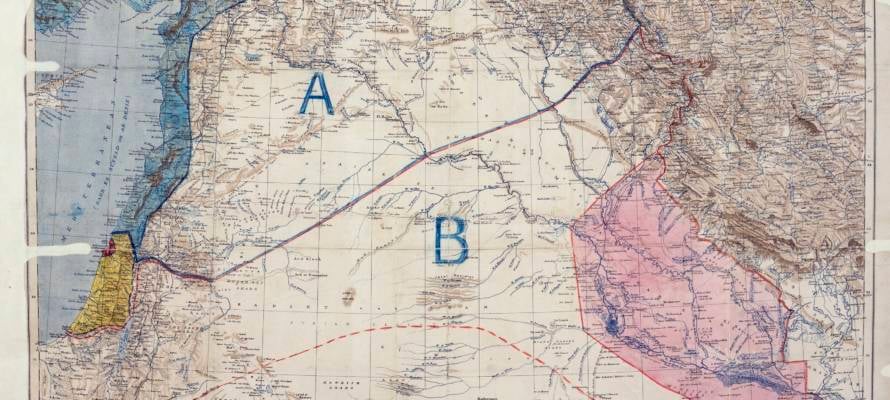

In its strictest and most precise sense, the term “Sykes-Picot” refers to the agreement reached in May 1916 between the British war-time diplomat Sir Mark Sykes and the French diplomat François Georges-Picot, regarding the future of the Fertile Crescent (the Levant and Mesopotamia) at the end of the war, on the assumption that the Ottoman Empire, Germany’s war partner, would be partitioned. The expanse was to be divided into British and French areas of direct control and influence, with Palestine becoming an international entity. Shaped by British strategic interests and France’s historic claim to a special position in the Levant, the agreement envisioned that Britain would have Mesopotamia and a land bridge to the Mediterranean, and France would have Lebanon and a large part of Syria.

The Sykes-Picot agreement was just one component of the secret war-time diplomacy regarding the Middle East. It was complemented by agreements with two other war-time powers interested in the region, Russia and Italy, as well as by a series of subsequent British actions and commitments, such as the Balfour Declaration and the correspondence with the Hashemite family. These and other changes notwithstanding, the term “Sykes-Picot” refers also to the overall peace settlement in the Middle East and to the political order it established.

The system that emerged from the final phase of the war and the peace-time diplomacy was in fact quite different from the reality envisaged by Sykes and Picot. One, Palestine on both banks of the Jordan became a British Mandate (on behalf of the League of Nations). Two, in an agreement between Lloyd George and Clemenceau, Mosul and northern Iraq were transferred from the French to the British area of control and were incorporated into the Kingdom of Iraq. Three, as part of the same agreement, Britain gave France a free hand in the area it acquired, which the French used to expand the area of Lebanon at Syria’s expense and divide Syria into several states. Four, Britain created the Emirate of Transjordan in order to placate the unhappy Abdullah and subsequently detached it from Mandatory Palestine. Five, the province of Alexandretta on the Turkish Syrian border was given a special status, and was eventually ceded by France to Turkey on the eve of World War II.

The Arab states created in this fashion – Iraq, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon – became part of a much larger system of Arab states, most of which had nothing to do with the Sykes Picot agreement.

In retrospect, this chain of actions and events looms as an egregious manifestation of European colonialism at its worst. Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon were historic and geographic terms, but the states that came to carry these names had limited relevance to realities on the ground. The creation of Greater Lebanon was a grave mistake that undermined the coherence and durability of the smaller Lebanese entity. The imposition of a Sunni royal family on an Iraqi state with a Shiite Arab majority and a large Kurdish minority was a recipe for instability. The policy of divide and rule and cultivation of minority groups in Syria was a major obstacle to the emergence of a Syrian entity. It was a mistake not to use the large area on both sides of the Jordan to create a clear distinction between an Arab and a Jewish entity. For their part, the Kurds remained without a homeland. These inauspicious beginnings were later exacerbated by the sway of pan-Arab nationalism, which contended that these were all Arab states. However, the quest to recognize the diversity of the Levant states and the need to accommodate this patchwork through the construction of pluralistic political systems lie at the root of the current turmoil.

The Legal Relevance of the Sykes-Picot Agreement (Robbie Sabel)

The 1916 British-French Sykes-Picot agreement defined future British and French spheres of influence in the Ottoman Empire. At the time, the agreement was legally binding on Britain and France, albeit conditional on the Allies defeating the Ottomans. The fact that it was secret and did not necessarily take into account the wishes of the local populations did not, under international law, affect the binding nature of the agreement.

In the treaties of Sevres (1920) and Lausanne (1923), Turkey renounced all claims to the Ottoman Empire outside the borders of modern day Turkey, in favor of Britain and France. Britain and France were thus legally entitled to deal with these territories. The 1916 agreement did not define in detail the borders of the areas concerned; this was done later by the British and the French in a series of agreements signed in 1922 and 1923 that defined the borders of Palestine (including what is now Jordan), Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. Their decision as to the borders of the territories was approved by the League of Nations, thus acquiring international approval of legitimacy, though legally their decision would have been binding even without the approval of the League.

In accordance with modern international law, new states automatically inherit boundaries created before their independence – uti possidetis. This rule has also been applied by Israel and its neighbors Egypt and Jordan in their peace treaties.

New states are free to agree on changes to colonial borders, but absent such agreement, the old colonial borders remain the default borders. The actual Sykes-Picot agreement has been superseded throughout the Middle East by subsequent agreements and developments, but the borders determined by Britain and France as a consequence of that agreement remain the default borders of the states in the area.

Is a New “Sykes-Picot” Possible in the Middle East? (Oded Eran)

The civil wars raging in recent years in some of the Arab states in the Middle East and the emergence of movements, motivated mostly by Islamic fundamentalism, challenge the current political configuration of the region and the supremacy of the state. It is difficult to imagine that the old order can be restored. Rather, in light of the different religious and ethnic realities in the region, a new, more representative order is required that must avoid creating miniscule states with little political and economic viability.

A combination of redrawn borders and use of new political formations that have not been used in the region, such as federation/confederation, may be required. It seems, however, that the fighting minorities, factions, and movements are not yet willing to consider the establishment of new permanent political arrangements in their own geographical environment, let alone redrawn borders. It may be premature and even counterproductive to publically discuss the agreed alteration of existing borders and replacement of the old order of a central government by a different system. It will also be futile to assume that some of the indigenous forces battling in the Middle East will be satisfied with simply returning to the status quo ante bellum.

The specter of two officials of extra-regional powers meeting secretly, dividing a region of the world between their own countries, and enshrining it in international treaties is now improbable. Yet an initial agreement in principle among the outside major players on a reconfiguration of the region will be necessary to make this change feasible. Syria and Iraq could become confederations without changing their current outside borders. Internal borders will be generally delineated, leaving details to negotiations between the future components of the new political structures/federal states. The proposed “new Sykes-Picot” will also include a broad division between the powers of the center and those of the units that will make the federal state.

It will be necessary to prevent regional players from trying to scuttle the outlines of a proposal in an effort to position the outside powers against each other and leave the region in chaos. It is therefore imperative that at least a broad understanding and/or agreement is reached between the United States, Russia, and the EU. Only then will key regional states such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Iran, and Turkey be brought in. At the third stage, some of the local players will be asked to give their consent.

It is clear that among the differences between 1916 and 2016 is the absence of an external power, capable of imposing a settlement – even if agreed on by the international community. The reluctance of the major players from outside the region to deploy forces on the ground removes a key tool in this respect. However, preventing weapons from falling into the hands of groups opposing a political settlement, stopping new volunteers from reaching local forces, and destroying arsenals and depots may well accelerate the willingness to consider compromises.

It may be too early to announce a new ‘Sykes–Picot,” but the time is ripe for international players to discuss the possible outlines of a new order in the Middle East, retaining the existing relevant parts and adding new ones, to accommodate the changes that occurred in the past 100 years.

The Israeli-Palestinian Angle

It is clear that when searching for a regional new order, the international community will not be able to avoid addressing the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Notably, the collapse of the old order in core areas of the Middle East has had contradictory effects on the Israeli-Palestinian impasse: it is clearly difficult to envisage an Israeli government taking risks in the present regional circumstances, but the current flux has created new space for creative ideas and solutions. Both Israelis and Arabs should bear in mind the fact that the Sykes-Picot order was an action of external powers tinkering with the region. A century later, the peoples of the region have a rare opportunity to shape their own history.

By: Itamar Rabinovich, Robbie Sabel and Oded Eran. This article originally appeared on www.inss.org.il