The black camera would go on to play a historic role in documenting the lives of the partisans in the forest.

By Etgar Lefkovits, JNS

Armed with only his camera, the Jewish partisan came up on the Ukrainian policeman guarding the ghetto in Nazi-occupied Poland and put the camera to his waist.

“If you shout, you die,” he told the officer.

Mistaking the metal of the Leica camera at his back for a gun, the Ukrainian policeman stayed silent.

It was the last days of 1942, and Edmund “Mundek” Łukawiecki had just rescued a young Jewish woman from the ghetto from the clutches of the Germans and their Ukrainian collaborators.

He would bring her to the forest to join the partisans; they fought the Nazis till the end of the war.

Edmund “Mundek” Łukawiecki (right) in a Polish forest during the German occupation. Credit: Courtesy of Yad Vashem.

A match made in the ghetto

The couple, the sole survivors of their families, would end up marrying after the war, but it was no love match and their relationship was more a business deal, their 77- year-old son Simon Lavee said in an interview with JNS.

His father had entered the Lubaczów Ghetto in southeastern Poland, intending to free his fiancée, but she, like the rabbinical elders from the Belz Chassidic group who were incarcerated there, were afraid to flee for the forests, Lavee said.

But his grandfather begged his father to take his daughter Chana Bern out and offered him some money for the service. “He didn’t do it out of love,” Lavee said. “It was a business deal.”

It was just in time.

Less than a week later, the liquidation of the ghetto began, and thousands were murdered in the ditches.

Chana Bern in a Polish forest during the German occupation. Credit: Courtesy of Yad Vashem.

The lives of the partisans

The black camera would go on to play a historic role in documenting the lives of the partisans in the forest.

Łukawiecki had bought the top-of-the-line German camera in the 1930s and studied with a photographer what started as a hobby and would turn into a lifelong career.

After the war broke out, he took his hobby with him. “He was always with the camera in one hand and a weapon in the other,” his son said.

After his foray into the ghetto, his father was charged with running a Jewish team of executioners within the Polish resistance army, focused on targeted assassinations of Nazi collaborators, members of the Ukrainian auxiliary police, and even German officers responsible for atrocities against Poles and Jews.

A Christian friend of his father, Józef Kulpa, hid the couple upon their escape from the ghetto and would develop the photos taken in the forests. In 2011, he was posthumously recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, for risking his life to save Jews.

After the war, the couple married and immigrated to Israel.

Łukawiecki used other cameras in his new life as he shot pictures of a rare snow in northern Israel shortly after the establishment of the State in 1948 or at his Tel Aviv studio, rarely speaking about the Holocaust or the vintage camera that saved their lives, which he stored away in their home.

Eight decades later, the camera along with a collection of 60 photos from his album has been donated to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, where it will be displayed at the Holocaust Remembrance Center’s state-of-the-art David and Fela Shapell Family Collection Center, which opens next week.

“We didn’t want it to end up at a flea market,” Lavee said.

The story of the partisan and his camera is also the subject of a book, “Jewish Hit Squad: Armja Krajowa Jewish Raid Unit Partisans,” that his son penned, and a documentary film, “The Partisan with the Leica Camera.”

Partisan Edmund “Mundik” Łukawiecki’s camera, June 26, 2024. Credit: Courtesy of Yad Vashem.

Still working

The black camera, which still works even as its dial is jammed and ever so slightly corroded, was being meticulously dusted in all its crevices by a preservation expert at the Jerusalem Holocaust Museum’s soon to be opened Collection Center at the new Moshal Shoah Legacy Campus during a tour arranged for JNS last week.

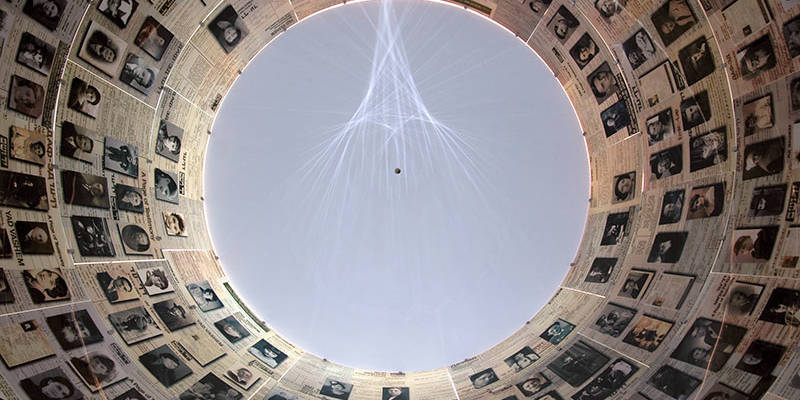

The five-story campus, which was built over the last couple of years with donations from families around the world, will house the world’s largest archive of Holocaust-era artifacts, photographs, artwork, and documentation.

The cutting-edge facility, which was built four levels underground so as not to overshadow the museum’s monumental Hall of Remembrance that it faces, has an oxygen reduction system to prevent fires along with a digital controlled system to ensure the best preservation of the collections in storage.

Nearly half of the items being preserved were donated in the decade since the project was first planned.

“It’s not a happy thing working about the Holocaust but then you realize the [importance of the] mission of keeping the memory alive,” said Medi Schved, director of the collections.

“The events of the last year only make our job more critical than ever,” said Maya Shaham, collections registrar. “It’s our Jewish story.”