Israel celebrated the rich and evolving history of its ancient language – Hebrew.

By: United with Israel Staff

With files from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Israel on Monday marked Hebrew Language Day, celebrated on the birthday of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the father of modern Hebrew.

The revival of the spoken Hebrew language is an extraordinary story, unparalleled in history. A language with roots dating back more than 3,000 years, it was brought back to life after centuries during which it effectively lay dormant, and it’s now flourishing in the 21st century.

Hebrew was not a spoken language 150 years ago. It was literally nobody’s mother tongue. Today, more than nine million people speak Hebrew and, for the majority of them, it’s their native tongue.

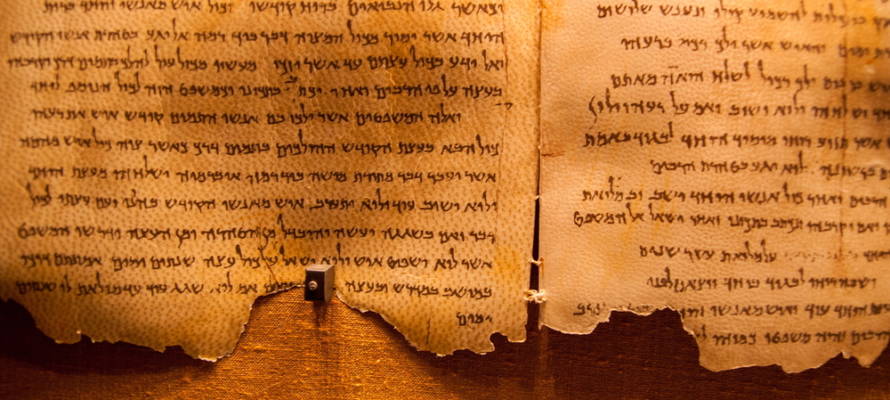

Throughout the millennia of the Jewish dispersion following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, Hebrew remained alive in liturgy and religious ceremonies and as a sort of lingua franca across the Diaspora.

Written Hebrew continued to evolve; it was the language of poetry and correspondence between scholars, who wrote books on law and philosophy in Hebrew.

Each generation was encouraged to be literate in Hebrew so as to be familiar with Judaism’s foundational texts and life-cycle traditions and rituals. But, during these years, the language ceased to be a living, breathing part of ordinary, secular personal or national life.

Part of Israel’s Creative Energy

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda was the driving force behind the revival of the ancient language and its transformation into its modern form. This visionary linguist, who was born in Lithuania in 1858, came to Israel in 1881 with a dream to transform Hebrew into a modern language and to make it the language spoken in every home in Israel.

He dedicated his life to the realization of his dream.

Ben-Yehuda campaigned to make Hebrew the language of instruction in Israeli schools, worked on expanding the Hebrew vocabulary so it could meet the demands of modern Israeli society, created the first modern Hebrew dictionary and edited the first Hebrew-language daily newspapers. His son, Itamar Ben-Avi, was the first child in modern times to grow up with Hebrew as his mother tongue.

Ben-Yehuda fashioned out of the ancient Hebrew structures over 300 new Hebrew words. Since then, more than 15,000 new words have been added, and we’re still counting.

The Academy of the Hebrew Language, established in 1949, has continued Ben-Yehuda’s efforts as the world’s premier institution for modern Hebrew, where new words and terms are created and standards are set for grammar, transliteration, punctuation and orthography. Located at the Givat Ram campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, its decisions are binding on all government agencies.

The revival of Hebrew as a spoken language is part of the creative energy which has always characterized the story of modern Israel. The Hebrew language is a rich, compelling expression of Israeli vitality and, at the same time, of the profound link between the Bible and the latter-day rejuvenation of the Jewish people in their ancient homeland. This is a story of national and cultural revival unparalleled anywhere else. And the realization of a vision that only a few generations ago would have seemed like a wild and impossible dream.

In his book Was Hebrew Ever a Dead Language?, British historian Cecil Roth summarized Ben-Yehuda’s impact on the Hebrew language as follows, “Before Ben‑Yehuda, Jews could speak Hebrew; after him, they did.”

Multi-Faceted Celebration

As part of Hebrew Language Day, the Knesset Library and the staff of the Knesset Records held on Monday an event at which former MK and Israeli ambassador to Japan Eli Cohen gave a lecture on Biblical Hebrew in Japanese; Prof. Michal Ornan Ephratt, a linguist, discussed silence as a means of expression; and journalist, author and linguist Rubik Rozental discussed tweeting in 144 characters.

As part of the event, the “Gnazim Archive Reveals” exhibit, on loan from the Eretz Israel Museum (in cooperation with the Gnazim Institute of the Hebrew Writers Association in Israel), was placed on display in the library’s reading room.