Israel’s National Library digitized a rare collection of communal ledgers from long-lost Jewish communities of Europe, offering the public a chance to study Jewish self-governance on the Continent.

By Associated Press

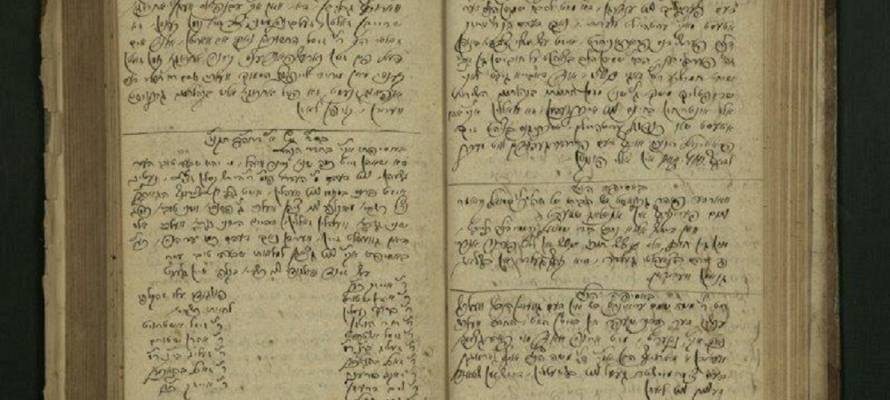

Israel’s National Library recently made available scores of documents, known as pinkasim, that were used by European Jewish communities hundreds of years ago to keep track of financial transactions, political happenings, relations with non-Jewish government bodies, and even funny moments.

Yoel Finkelman, curator of the library’s Judaica collection and manager of the project, said Tuesday that any Jewish community with a governing body had a pinkas, making the ledgers “some of the most significant documents for understanding early modern Jewish European history.” He said that currently they also are some of the least accessible.

Today, the ledgers that have survived are held in various collections around the world. The first phase of the project , funded by the Rothschild Foundation Hanadiv Europe, has uploaded around 200 documents from the years 1500 to 1800. The library hopes to collaborate with other institutions to make more available online.

Finkelman said that during the period covered by the collection’s documents, the continent saw a rise of formal bureaucracies. It also was a time in which Jewish populations lived relatively autonomously. This resulted in an era in which formal communal institutions played a uniquely important role in Jewish European life, he said.

During the 1800s, Jews became more integrated into European societies, reducing the role of communal self-governance.

Many Jews left eastern Europe late that century to flee persecution or to seek economic opportunities abroad. Some six million Jews, or two-thirds of the European Jewish population, were killed by the Nazis and their collaborators in the Holocaust during World War II.

For the general public, accessing a ledger online will not necessarily make it easier to read about Jewish history. They often mixed several languages including Hebrew, Yiddish, Polish and others, at times in a single sentence. At the moment the library does not have plans to translate them.

“Putting them up online is a necessary step for them to get the attention they deserve by historians and through historians to public discourse,” said Finkelman.