“Within a decade, I hope we will be able to increase fertility among older women using anti-viral drugs.”

By Pesach Benson, United With Israel

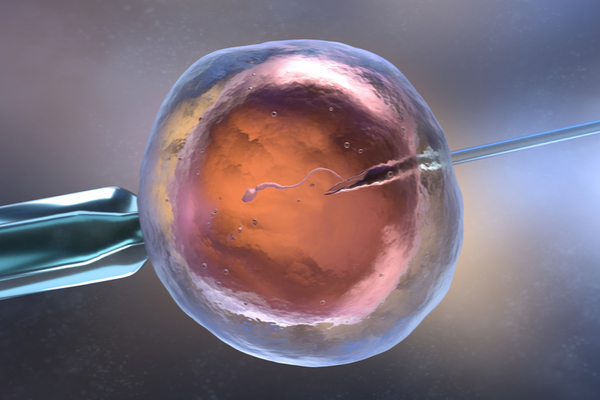

Throughout much of the world, increasing numbers of women are delaying having their first child until they are in their late thirties and even their forties. At this age, their eggs are rapidly deteriorating and, even with modern IVF treatment, the prospects of conception are far from guaranteed.

But what if an egg’s deterioration process could be reversed?

That’s the goal of molecular biologist Dr. Michael Klutstein, head of the Chromatin and Aging Research Lab in the Faculty of Dental Medicine at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU).

This possibility came one step closer with recent research from his lab, carried out by PhD student Peera Wasserzug-Pash. in collaboration with clinicians from Hadassah Medical Center and Shaare Zedek hospitals. Their findings were published in Aging Cell, a peer-reviewed monthly journal.

In a sense, the deterioration of eggs actually begins the moment a baby girl is born. Women are born with approximately one million eggs in their ovaries, sometimes more. But by the time a woman reaches puberty the number of viable eggs dwindles down to roughly 300,000.

Of those, 300-400 will be ovulated — released into the fallopian tubes where an egg can be potentially fertilized by sperm.

However, a woman’s egg cells begin to accumulate damage to their genetic material when a woman is relatively young. By a woman’s late-thirties, her eggs have accumulated so much damage to the DNA that they are unable to mature and be fertilized.

Moreover, for every egg that ovulates, an estimated 1,000 die each month. And as a woman ages, that number accelerates. When a woman runs out of viable eggs, the ovaries stop producing the estrogen hormone and her body begins going through menopause.

Anti-Viral Drugs Reversed the Deterioration

Dr. Klutstein’s team successfully identified one of the aging processes that prevent the successful maturation of an egg cell. Most importantly among them is the loss of the regulation processes that normally stop the damaging parts of DNA from becoming active.

Klutstein and his HU team’s research, using mouse and human egg cells, not only identified the details of these processes but showed how they are interrelated and ultimately prevent an egg cell from maturing.

To confirm their findings, the team then used chemicals that mimic the actual processes that stop repression of sections of the egg cell’s DNA and liberate the DNA-damaging viruses.

Reproducing the aging processes artificially enabled the team to link the processes of loss of genomic regulation and the expression of damaging elements in aging egg cells.

The final stage of their research tested ways to reverse the destructive aging processes at work in an egg cell. If viruses or parts of viruses were released and activated in aging eggs, then perhaps anti-viral drugs could prevent this process and the resulting damage.

In their paper, the researchers showed that anti-viral drugs did indeed reverse the process in mouse egg cells and returned to their former youthful selves. There has also been similar success using genetic manipulation to insert two genes into the mouse egg cell DNA – the implanted genes produce enzymes which prevent the chain of events that leads to the activation of the damaging parts of the DNA.

“Within a decade, I hope we will be able to increase fertility among older women using anti-viral drugs,” Klutstein said.