Israeli archaeologists’ discoveries related to the Black Plague pandemic in the 6th century reveal critical findings about economic collapse in the face of a major pandemic.

By Yakir Benzion, United With Israel

Israeli archaeologists recently made major discoveries related to the Black Plague pandemic’s impact on the Holy Land in the 6th century, which also shed light on the current coronavirus crisis gripping the world.

This team investigated why a 6th-century agricultural settlement in the Negev desert was abandoned, making discoveries that provide insight into what is happening to the world in the 21st century.

The archaeologists hail from several universities and the Israel Antiquities Authority, and they focused on the ancient town of Shivta, not far from Gaza. While the ruins of Shivta indicate a glorious past, it all came crashing down in the 6th century, and the researchers wanted to know why the settlement was abandoned.

What Happened?

As in many archaeological digs, answers were found in the garbage.

“Your trash says a lot about you,” explains Prof. Guy Bar-Oz of the University of Haifa. “In the ancient trash mounds of the Negev, there is a record of residents’ daily lives – in the form of plant remains, animal remains, ceramic sherds, and more.”

The team excavated the mounds to deduce the human activity behind the trash, then tied that to two key events of the 6th century: the Black Plague, which spread throughout the Byzantine Empire in 541 CE, and a devastating volcanic eruption in late 535 or early 536 CE that resulted in a planet-wide temperature drop for 10 years.

Scholars disagree as to just how far-reaching and devastating the mid-6th century epidemic and climate change were, just like politicians today are fighting over what effects COVID-19 and climate change are really having.

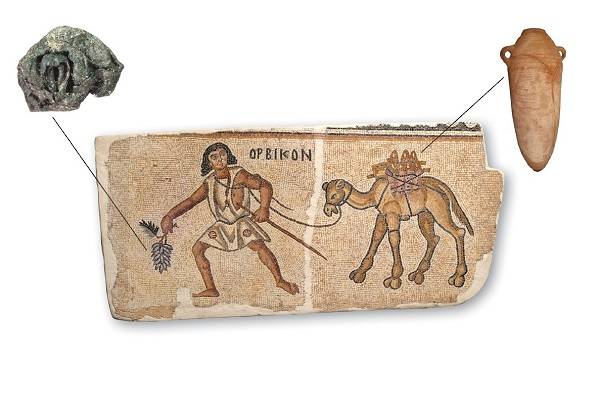

Byzantine texts praised “Gaza wine” that was exported throughout the region and transported in “Gaza wine jars,” remnants of which were dug up in the Shivta mounds in high quantities.

Bar-Ilan University PhD student Daniel Fuchs checked out the grape pips (seeds) in the rubbish, discovering a significant rise in the ratio of grape pips to cereal grains between the 4th and mid-6th centuries that suddenly declined. The team then evaluated changes in the ratio of Gaza wine jars to bag-shaped jars that transported other goods.

They found the rise and fall of the use of Gaza wine jars matched the rise and fall of the grape pips, connecting this to Mediterranean trade in wine and shedding new light on international commerce 1,500 years ago.

Researchers realized the plague resulted in a high death toll in Byzantium and other parts of the empire. Like the tourism industry that has been shocked by the COVID-10 pandemic, the plague caused a major drop in demand.

That in turn would have detrimentally impacted the Negev economy, even while trade in nearby Gaza may have continued. This appears to have been coupled with the volcanic eruption that is thought to have filled the air with so much volcanic dust that it caused a decade-long global cooling and may have increased precipitation, including flash flooding that could have damaged local agriculture.

Devastating Economic Blow

Sorting and counting 1,500-year-old grape seeds may not appear to be the most exciting activity, but the research on archaeological plant finds demonstrates the ingenuity and insight involved in ancient peoples’ interactions with plants.

“It appears that agricultural settlement in the Negev Highlands received such a blow that it was not revived until modern times,” Bar-Oz said, noting the decline came nearly a century before the Islamic conquest of the mid-seventh century.

The two likely triggers for the mid-6th century collapse – climate change and plague – reveal inherent vulnerabilities in political-economic systems, then and now.

“The difference is that the Byzantines didn’t see it coming,” explains Fuchs. “We can actually prepare ourselves for the next outbreak or the imminent consequences of climate change. The question is, will we be wise enough to do so?”

United with Israel extends a special note of appreciation to the Genesis Prize for their generous support.