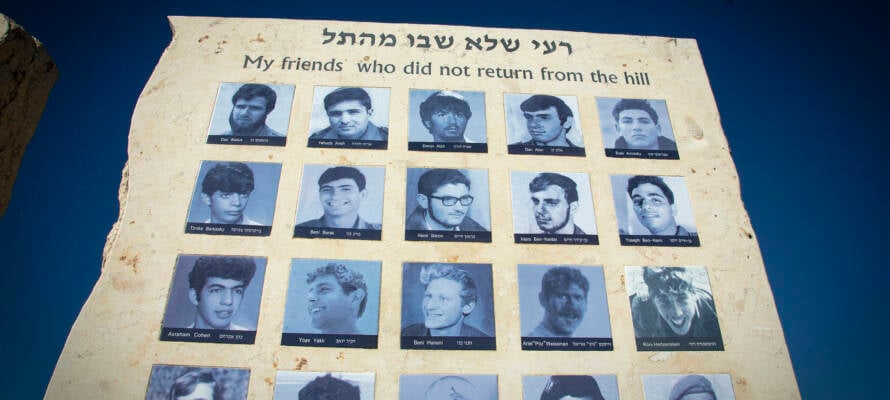

A “little bloodied”? Try 2,656 dead Israeli soldiers.

By Moshe Phillips

In recent days, there have been numerous articles, seminars, and lectures in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of the Yom Kippur War. Yet, somehow, they all managed to miss one of the most crucial aspects of the conflict: how Henry Kissinger prevented Israel from launching a preemptive strike.

On Yom Kippur morning, hours before the 1973 Arab invasion, Prime Minister Golda Meir was informed by her military intelligence officials that Egypt and Syria were massing their troops along Israel’s borders and would attack later that day. The Israelis immediately contacted Kissinger.

Matti Golan, longtime chief diplomatic correspondent for Ha’aretz, described in his book “The Secret Conversations of Henry Kissinger” what happened next:

“Till the very outbreak of the fighting, Kissinger remained more concerned with the possibility of an Israeli preemptive strike than an Egyptian-Syrian attack.” Kissinger instructed the U.S. ambassador in Israel to personally deliver to Mrs. Meir a “presidential entreaty” —that is, a warning, in the name of President Nixon—“not to start a war.” (page 41)

Abba Eban, who was then Israel’s foreign minister, confirmed in his autobiography that Israeli Army Chief of Staff David Elazar proposed a preemptive strike, but Prime Minister Meir and Defense Minister Moshe Dayan rejected it on the grounds that “the United States would regard this as provocative.” (page 509)

Further confirmation comes from the widely acclaimed book, “The Prime Minister,” by the late Yehuda Avner, a distinguished Israeli diplomat who witnessed Kissinger’s actions up close.

Avner (1928-2015) was a speechwriter, secretary, or adviser to five different Israeli prime ministers, from both sides of the political spectrum—Golda Meir, Levi Eshkol, Yitzhak Rabin, Menachem Begin, and Shimon Peres. He also served as Israel’s ambassador to various countries, as well as other senior diplomatic positions.

Avner bluntly wrote that American officials—meaning Kissinger—“tied” Golda’s hands on the eve of the Yom Kippur War, telling her “in no uncertain terms not to fire the first shot.” They even “warned” her “against full-scale mobilization” of Israel’s reserve forces.

Kissinger did not want Israel to win a decisive victory because he thought that would make it hard to wring concessions out of the Israelis after the war. Having prevented Israel from striking first, Kissinger then exploited Israel’s suffering in the early days of the war in order to advance his strategy.

The Israelis immediately requested a U.S. airlift of military supplies. But Kissinger stalled them—for an entire brutal week. Kissinger’s plan was to orchestrate “a limited Egyptian victory,” according to David Makovsky, formerly an Obama Administration Middle East envoy. Writing in the Jerusalem Post in 1993, Makovsky confirmed that the secretary of state feared an Israeli victory “would cause Israel to strengthen its resolve not to make any territorial concessions in Sinai.”

Walter Isaacson, in his definitive biography, “Kissinger,” confirmed: “Kissinger opposed giving [Israel] major support that could make its victory too one-sided.” Kissinger told Defense Secretary James Schlesinger that “The best result would be if Israel came out a little ahead but got bloodied in the process.” (page 514)

Back to Avner’s “The Prime Ministers.” Avner quoted from a conversation between Kissinger and President Richard Nixon on the ninth day of the war. Israel was begging for U.S. weapons. Kissinger, with Nixon’s agreement, was still stalling on the weapons shipments. “We’ve got to squeeze the Israelis when this is over and the Russians have to know it,” Nixon said. “We’ve got to squeeze them goddamn hard.”

Kissinger replied: “Well, we are going to squeeze them; we are going to start diplomacy in November after the Israeli elections.” And squeeze them he did, pressuring the Israelis to release the encircled Egyptian Third Army and various other concessions.

The process culminated in early 1975, by which time Nixon had resigned and Gerald Ford was president—but Kissinger was still directing America’s Middle East policy. When Israel’s new prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, hesitated to give into Kissinger’s demands for more territorial withdrawals, the secretary of state orchestrated what Avner called a “brutal” message from President Ford to Rabin. The message blamed Rabin for the absence of peace and announced a “reassessment” of America’s policy toward Israel. The “reassessment” consisted of a cut-off of all U.S. weapons shipments. Within months, Rabin surrendered to the pressure.

It’s troubling that so many descriptions of the Yom Kippur War skip over these crucial events. Fortunately, we have the accounts by Yehuda Avner, Matti Golan, Abba Eban, David Makovsky and Walter Isaacson to set the record straight.

Moshe Phillips is a commentator on Jewish affairs. He was previously a U.S. delegate to the World Zionist Congress.