Born in Prague, Peter Buxtun was a baby when the Sudetenland, the German-speaking part of Czechoslovakia, was ceded to Nazi Germany.

By Andrew Silow-Carroll, JTA

In the early 1960s, Peter Buxtun was tracing sexually transmitted infections for the U.S. Public Health Service in San Francisco when he wandered into the coffee room of his clinic.

There he heard an older PHS officer talking about a study begun 30 years before.

What he heard alarmed him: Working with the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, the government had recruited 399 Black men who had contracted syphilis.

Although antibiotics became available in the 1940s that could treat the disease, federal health officials ordered that the drugs be withheld from the subjects in order to study the effects of the disease.

The revelation jogged something in Buxtun, who was born in what is now the Czech Republic to a Jewish father and a Roman Catholic mother.

Buxtun grew up listening to tales of the Holocaust told by an uncle, a German officer who tried and failed to prevent Nazi soldiers from murdering civilians.

“I thought, we can’t be doing this,” Buxtun recalled, according to historian Susan Reverby.

He made his way to the library where he studied the Nuremberg Doctors Trial and the Nuremberg Principles, ethical guidelines for medical treatment and research developed in the wake of the Nazis’ monstrous experiments on Jews and and other prisoners.

Buxtun recalled, “It was toward the end of the evening in that library downtown, and I thought: I’ve got to do something.”

The report he wrote in November 1965 to the Centers for Disease Control and the PHS blew the whistle on one of the most notorious research projects in the history of U.S. public health.

Although it would take five more years and an Associated Press exposé to bring his findings to light, Buxtun would demonstrate that the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” was a shameful abuse of government authority and medical ethics.

The revelations led to Congressional hearings and a class-action lawsuit that resulted in a $10 million settlement and the study’s closure.

In 1997, President Bill Clinton formally apologized for the study, saying it was “wrong — deeply, profoundly, morally wrong. It was an outrage to our commitment to integrity and equality for all our citizens.”

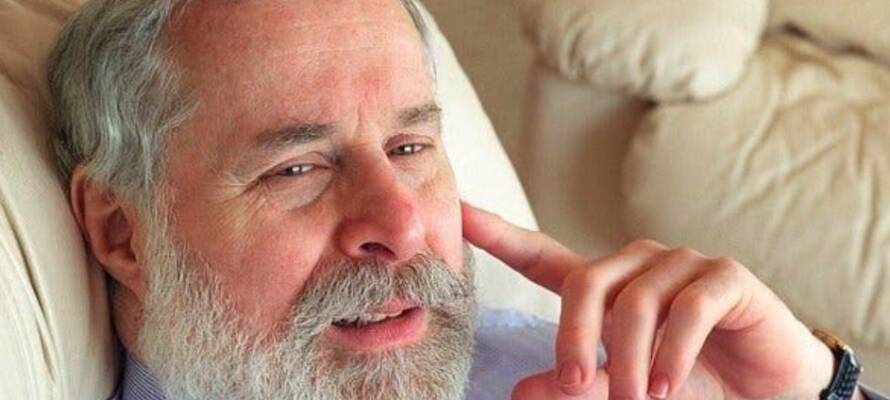

Buxtun died from Alzheimer’s disease in Rocklin, California, on May 18, although his passing was only reported this week. He was 86.

The results of his act of conscience were profound. The government put in place new rules about how it conducts medical research. Some African Americans remain reluctant to participate in medical research to this day.

In interviews, Buxtun would shrug off the accolades he later received for his whistleblowing, including from family members whose relatives had taken part in the study.

“I don’t want to be embarrassed by an oversupply of compliments. I am who I am,” he told bioethicist Carl Elliott in 2017.

But he would go on to give presentations about the study and medical ethics, and win awards for his involvement in exposing the Tuskegee study.

After leaving the Public Health Service he attended law school, travelled frequently, and collected and sold antiques.

Born in Prague, Peter Buxtun was a baby when the Sudetenland, the German-speaking part of Czechoslovakia, was ceded to Nazi Germany.

Buxtun’s father immediately prepared the family to immigrate to the United States, where they settled on a farm in Oregon.

Buxtun attended the University of Oregon, and served in the U.S. Army as a combat medic. He was working as a social worker when he answered an ad for the PHS.

In addition to his advocacy, he spent more than 20 years trying to recover his family’s properties confiscated by the Nazis, and was partly successful. He left no immediate survivors.

“Peter’s life experiences led him to immediately identify the study as morally indefensible and to seek justice in the form of treatment for the men,” Ted Pestorius, a deputy director at the CDC, said at a 2022 program marking the 50th anniversary of the end of the study. “Ultimately, he could not relent.”