Museum CEO calls the mosaic ‘the greatest discovery since the Dead Sea Scrolls.’

By Menachem Wecker, JNS

For hundreds of years, a mosaic lay hidden in Megiddo in northern Israel until, in 2005, it was found and preserved as a local prison sought to expand. The mosaic recently made the trip—in nearly a dozen pieces—across the ocean to Washington, D.C., where it is on exhibit at the Museum of the Bible.

At an opening reception for the exhibit on Sunday afternoon, Carlos Campo, CEO of the museum, said that the mosaic, which dates to around the year 230, like an Impressionist show that opened recently at the nearby National Gallery of Art, requires stepping back to take in the broader, unifying picture.

“Frankly, I’m still stepping back, because as I step back, I learn more about the power of this object and what it’s trying to say to me about ancient history, about the history of Christianity, about the place in Israel and so much more,” Campo said.

“This object really is a way for us to come together—a way for us to see that these tiny little tesserae, these tiny little chips, these beautiful pieces when placed together—they tell a remarkable story of unity,” he told those assembled.

“We truly are among the first people to ever see this, to experience what almost 2,000 years ago was put together by a man named Brutius, the incredible craftsman who laid the flooring here.”

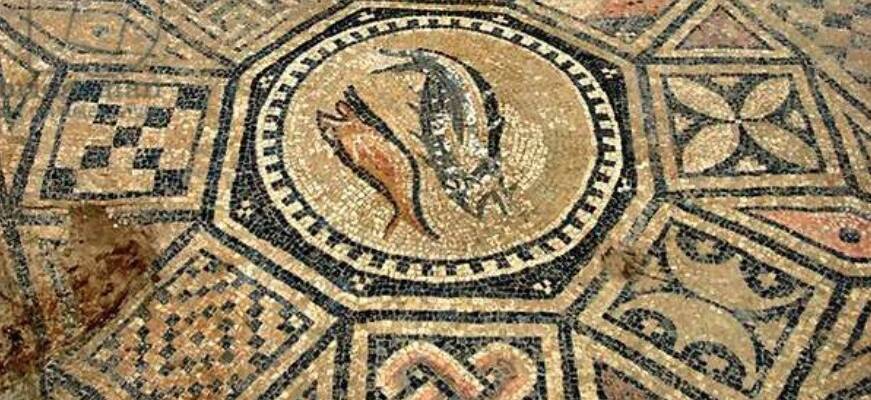

The mosaic, which contains a very early mention of the name of Jesus and includes an illustration of two fish, as well as a variety of geometric patterns, is “the greatest discovery since the Dead Sea Scrolls,” Campo said.

(The exhibit “The Megiddo Mosaic: Foundations of Faith” is on view until July 6, 2025.) Gil Lin, the head of the Megiddo Regional Council, agreed in his address at the reception.

“The Megiddo mosaic represents the most significant archaeological find since the Dead Sea Scrolls,” Lin said. “For billions worldwide, it’s not merely an artifact but a tangible link to shared history, tradition and faith.”

The “priceless treasure from antiquity” will return home and will be installed where it was found and where it can be best appreciated, he promised. “Megiddo will do everything to build an ideal home for the Megiddo Mosaic and preserve this invaluable piece of history,” he said.

“Israel’s rich history has yielded countless archaeological wonders, yet even our most seasoned historians stand in awe of this remarkable discovery,” he added. “My father used to say, ‘If these floors could share their past.’ Well, in Megiddo, they never stop talking.”

A portion of the mosaic (including a very early reference to Jesus), dated to about the year 230, on view in the exhibit “The Megiddo Mosaic: Foundations of Faith” at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 15, 2024. Photo by Menachem Wecker.

Eliav Benjamin, deputy chief of mission at the Israeli embassy in Washington, said at the reception that the “extraordinary artifact” reflects “the deep connections that unite us all, our nations, our people over history across the globe.”

“This is probably one of the best well-kept secrets not just in Israel but in the entire world until now,” he said. “So definitely a special occasion now to have it exposed for the first time. People in Israel haven’t seen it. People in the world haven’t seen it.”

He noted that the symbol of the fish in the center of the mosaic, which scholars think may refer to fish as symbols of Christianity, is on display in Washington as the High Holidays approach, and that the fish head is a Rosh Hashanah symbol for “a new beginning and a good start.”

“This definitely is time for this, too,” he said.

Also in line with the approaching Rosh Hashanah holiday, there was a recitation of the Shehechiyanu blessing at the ribbon cutting that opened the show.

A rendering of the prayer hall at Kefar ‘Othnay (by Evolve Studios), which included the mosaic, dated to about the year 230, on view in the exhibit “The Megiddo Mosaic: Foundations of Faith” at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 15, 2024. Photo by Menachem Wecker.

‘Like a carpet’

Alegre Savariego, curator of the Rockefeller collection and mosaics at the Israel Antiquities Authority who worked on the exhibition, told JNS that the most important thing for viewers to take away from the show is the significance of one of the inscriptions.

“We found the name of Jesus before Christianity was part of the Roman empire,” she said.

The inscription is the second one to be found naming Jesus after a church in Dura Europos in present-day Syria, Savariego told JNS. She said that mosaics in this time period were meant to adorn floors.

“All the mosaics in the Roman period and the Byzantine period are just like a carpet—that you walk over it,” she said.

JNS asked if religious people at the time would have found it anathema to tread on sacred symbols, and might have preferred instead to walk around religious symbols or divine names.

Savariego said ancient people didn’t have such a concern and would have walked on the mosaics and would have sat around them.

It is significant, she told JNS, that four women are named in the mosaic, as is the man who created the mosaic. The women could have been martyrs or could have been significant in other ways.

“We don’t know for sure,” Savariego said. “It doesn’t say what they are doing there.” It’s also unusual to have so many women named. “Not like this together,” she said. “You will have one sometimes, but not four.”

A touchable model of the mosaic, dated to about the year 230, on view in the exhibit “The Megiddo Mosaic: Foundations of Faith” at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 15, 2024. Photo by Menachem Wecker.

The artist being named is also noteworthy. “Usually, you don’t have it,” she said. “This is the only one in Israel.” One of the inscriptions on the work notes that “Brutius has carried out the work.”

“The artists who created mosaics were a skilled workforce in the Roman Empire. Despite the practical and decorative value their work brought to Roman structures, only about 100 of them signed their work,” a wall text in the exhibit states.

The exhibit contains stones, which viewers could handle and which they might find lighter and more fragile than expected, that are of the variety that are included in the mosaic.

The entire mosaic is original, although a large set of stones in the middle of the floor is a replica. Scholars think that the original set of large stones, which is in Megiddo, was the base of a table, perhaps for use during the celebration of Communion.

“We archaeologists like to speculate a lot, and we have a good imagination,” Savariego told JNS. But she thinks it’s clear that there would have been a table in the middle of the mosaic floor.

‘You can’t erase history’

Savariego was also involved in curating the long-term exhibit “The People of the Land: History and Archaeology of Ancient Israel,” located not far from the Megiddo show at the Bible Museum.

It is very important for Israel to get to tell its own story in that gallery, according to Savariego, who told JNS that press coverage often distorts the Jewish state.

“The news is not really objective,” she said. “We always try to be objective, to bring the archaeology and the history of Israel, and this is very important.” “This is what we are,” she said. “Not just the bad things.”

Savariego noted that archaeological evidence demonstrates that Jews, Christians and Muslims interacted peacefully in the Negev, in the southern part of the Holy Land, in the sixth and seventh centuries.

“We are not colonizers,” she said. “We do have history, even if they don’t like it, we do have it.” “We were always working together,” she added. “You cannot erase the history.”

In the exhibit at the Bible Museum, that history almost was a non-starter. Campo, the museum CEO, shared photos during the opening reception of the boxed pieces of the mosaic just barely fitting, with four men holding it on a slant, through the door to the exhibit.

“That’s a close fit, buddy,” Campo said.