The Jewish presence in Kfar HaShiloach dates back to 1881, which at its height ran five synagogues and numbered some 160 families.

By Aryeh Savir, TPS

Original documents belonging to Yemenite immigrants to Israel from the 1880s who lived in the Kfar HaShiloach neighborhood of Jerusalem were recently discovered and brought to light. The documents are thrilling testimonies of Jewish life in the neighborhood – known as Silwan in Arabic – situated right outside the walls of Jerusalem’s Old City.

The Jewish presence in Kfar HaShiloach dates back to 1881, when Yemenite Jews came to Jerusalem and established a community, and at its height ran five synagogues and numbered some 160 families.

Encountering Arab violence and attacks for several years, the community was forced to finally abandon the area in 1939, and the synagogues were desecrated by Muslim attackers.

Israel reunited its capital in 1967, and the Jews began to return to the area some 20 years ago, reacquiring one property after another, including some of the synagogues.

The newly discovered documents were part of an estate left by Mazal Cohen, a member of the Tabib family, a Palmach fighter who was a candidate to light a beacon in 2017 during Israel’s 69th Independence Day ceremony. They were handed over by her son Ronen Cohen to Gadi Bashari, chairman of the Kfar HaShiloach Public Council and member of the board of directors of the Zionist Archives.

Cohen recalled that while taking care of his late mother in her last months, he came across “a swollen bag of yellowing documents folded together.”

“Slowly, I separated the pile of documents, which included pictures that shed light on the story of the Tabib family in the Jewish village of Shiloach and the community life there. This revelation connected me and my family to my grandparents and the Yemenite community of Olim, who came among the pioneers of the First Aliyah and settled in the Shiloach village,” he explained.

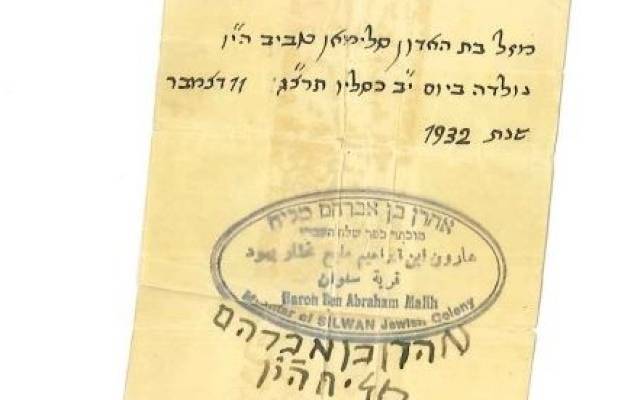

One of the documents is Mazal’s birth certificate, signed by the Yemenite village’s Mukhtar (village chief) Aharon Maliach. Another document has details regarding the family’s tax payments to the village committee and to the British Mandate’s government.

Another document, from 1942, is a confirmation from Maliach, apparently to be presented to the British police who prevented the Yemenite Jews from entering the village after its evacuation in 1938. The confirmation was given to Mazal’s father, Shlomo Tabib, who wanted to enter the village to dismantle iron and wooden planks from his house to use them as construction materials.

Yet another document from 1951 attests to the existence of an ancient Yemenite Torah scroll that Shlomo Tabib brought with him from Aden, Yemen, and passed it to a member of his family who also came from Yemen in those years, to care for and preserve.

Copies of the documents will be transferred to the Public Council archives and displayed in the visitors’ center of the ancient Ohel Shlomo synagogue, in the Shiloach village.

Bashari said excitedly that “for decades, these documents have been kept in the home of the deceased. These many testimonies of the Jewish life in the village are so thrilling, since they renew, in the most tangible way, the connection between the two generations: the original residents of Kfar Hashiloach and us, who follow in their footsteps and continue their way and their heritage.”

The documents “will reveal to the future generations many new aspects of the story of the village that existed at the foot of the City of David and the Old City of Jerusalem,” he said,

Cohen expressed hope that the documents, “which are written in the curly Rashi script, and some of which I have not yet deciphered, can reveal to others another piece of the story of this amazing community, and pay them the respect that they deserve.”