From the Finnish Air Force to major clothing brands, people are still using swastikas and other Nazi images in 2020, but risk condemnation for doing so.

By Yakir Benzion, United With Israel

For most people in the Western world the swastika is a symbol of penultimate evil that stirs revulsion of and loathing for the brutal Nazi era when the genocidal monster Adolf Hitler tried, but failed, to wipe out the Jewish people.

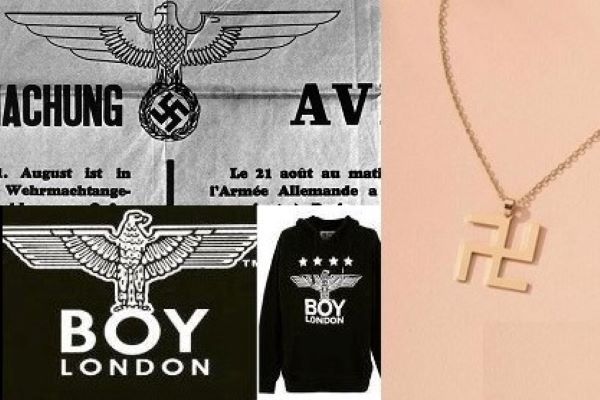

Notwithstanding the swastika’s lasting associations, retailers such as Shein continue to manufacture and market products incorporating the symbol.

Last week, Shein was forced to issue a public apology after putting a swastika necklace on its website.

“We made a gigantic mistake by selling a product that’s hurtful and offensive to many of you, and we’re so, so sorry,” the company said on its Instagram account, explaining that it was “a Buddist swastika necklace.”

Shein added, “There’s simply no excuse for our lack of sensitivity.”

Several years earlier, the popular UK brand Boy London was slammed for a logo that Jewish shoppers said bore a striking resemblance to a Nazi spread-winged eagle insignia known as the Third Reich’s Parteiadler symbol.

At the time, Boy issued a statement saying that “the brand is in no way connected to Nazism or the idea of anyone being discriminated against for their creed, colour or religious beliefs,” claiming that the logo “was inspired by the eagle of the Roman Empire as a sign of decadence and strength. Its aim is to empower people rather than oppress.”

Ironically, the brand was launched in the 1970s as a punk label by an Israel-based businessman named John Krivine, who sold the company in 1984.

In a more recent incident, Finland removed the swastika that had been part of the an air force symbol since 1918, several years before Hitler adopted the German “hakenkreuz” – or hooked cross – as the Nazi symbol. After decades of trying to keep the pre-Nazi era symbol, Finnish officials finally realized that their swastika was “causing misunderstandings” with other nations.

The U.S., for its part, is currently in the grips of a society-wide debate regarding the removal Confederate symbols, 155 years after the slavery-supporting Confederacy was defeated in the Civil War. Moves to rid the southern United States of the Confederate flag, which has become widely seen as not just the flag of the southern states, but also as a symbol of racism, have met resistance in some quarters.

Returning to the swastika, before the Nazis hijacked the swastika, it had been used for ages as a religious symbol, mostly in Asia before working its way up to Europe and being used by numerous cultures from the Greeks to the Vikings. The symbol is still widely used in in Hindu and Buddhist countries such as Nepal, India, and countries of southeast Asia.

But for Westerners, the swastika remains the embodiment of evil. For Jews it is the ultimate symbol of the threat of total annihilation – the goal of Hitler’s Germany. For those in the allied countries that fought and defeated the Nazis, it is the symbol of the evil enemy that sought to dominate and in many cases enslave them.